The Steelhead Story

It was a mild afternoon late in the winter of 1969 – a big snow winter on the South Coast. I’d finished a good day of steelheading on Nanaimo River and dropped into Johnson’s Hardware to brag. “Hit nine fish between the Willow and Haslam Runs and a couple were real sharks”. Ernie Johnson just shrugged. “You young guys just don’t know” he said. “Years ago you could catch forty on a good day”. He had the photos to prove it. Dog eared slaughter shots that would produce howls of outrage today. “Yeah, there were sure lots of fish in those days” I agreed.

But there weren’t; not in the way it seemed.

Few people fished for steelhead in BC before the 1960’s. Winter fish were ghosts of grey days and murky rivers. Most summer steelhead streams were remote and little known. Specialized steelhead tackle was still in the future. The early days were heady for the few angles who fished steelhead. Imagine having a lovely river like the Cowichan almost to yourself. Herman Mayea, a pioneer Cowichan steelheader can. “I remember one year back in the fifties when I had a contest with my fishing partner. I caught 300 but he caught more than 500.”

It’s not surprising that steelhead were thought to be abundant in the past. This misconception was one of several that led to the perilous situation in the mid seventies when steelhead numbers became dangerously low in many streams.

It was aided by information from American rivers where steelhead were more abundant. Lacking research of our own, B.C. relied on US knowledge. But steelhead streams to the south are different. Aside from Northern Washington, their basins were never heavily glaciated, their watershed soils are deeper and richer and climate and terrain are less harsh allowing the fish a longer growing season and better access to the upper reaches of rivers.

Many BC coastal streams drain short, steep basins of gravel and granite where run off is super charged by heavy rain and snow melt which causes wild flow fluctuations. The water is often cold even in the summer months and ice can be a factor in the winter. Nutrients are sparse and waterfalls often block passage a short distance from the sea. Young steelhead in the Northwest States usually smolt in their first of second year while many BC juveniles don’t head to sea for three or even four years. Every year they spend in freshwater takes a toll.

In short, most of our steelhead streams are much less productive than those to the south and where we thought we had thousands of fish, we had hundreds. Where we thought there were hundreds, there were tens.

Aside from a few premium streams like the Cowichan, the Stamp the Gold, the Dean and the Bella Coola in their good days, most of our streams carry a few hundred steelhead. With the forty fish annual catch quota before the mid-seventies, a few good steelheaders could easily catch most of the run. But steelhead research was thin in BC and American data was solid. What difference could a few hundred miles make?

By the mid –seventies, steelhead were falling back in many of our streams. Two fortunate circumstances combined to propel their recovery:

- Steelheaders began to lobby for catch and release and reduced kill. Some steelheaders began asking for a much reduced kill as early as 1969. In 1970, the Steelhead Society of BC was formed. Steelheaders like Barry Thornton, Earl Colp and Ted Harding Senior not only lobbied for better angling regulations but they were instrumental in helping to improve forest policy and practices around streams and reducing the commercial interception of steelhead.

- The Salmonid Enhancement Program(SEP) began in 1977

In my opinion steelheading has always attracted many anglers more interested in quality fishing rather than filling the freezer so it didn’t take much for steelheaders to demand more careful management of their resource when it appeared to be in trouble. Many anglers practised catch and release long before it became law. SEP provided funding for population surveys which quickly revealed that steelhead were by no means abundant. Prior to snorkel counts, the only available indicator of steelhead abundance in BC was the steelhead harvest analysis which was based on an angler questionnaire rather than direct observation.

More careful regulation began in 1977 when the annual catch quota was reduced from forty to twenty. It was then quickly reduced to ten and catch and release, barbless hooks and bait bans followed and have persisted to this day along with total closure in some cases.

Steelhead numbers were thought to have bottomed out in about 1979 and the 80`s were a period of recovery. In 1985, I spent a lot of time fishing the Riverbottom Reach at my friend Linda McLeod`s. She had lived there for ten years and had never caught a steelhead despite putting in lots of effort. She believed catching a steelhead was beyond her even though her yard fronted on Asha`s Run, one of the river`s best steelhead holding areas. In 1985, she caught over fifty and her nine year old daughter even caught several. I lost count of those I caught.

The bonanza was very gratifying but it didn`t last. By the 1990`s fish were dropping off again and scientists were beginning to realize that ocean conditions were a strong factor in salmonid survival. Many had thought that if the freshwater environment was protected and fostered, steelhead numbers would hold. A lot of effort was put in to careful catch regulation and habitat protection and more effort was expended on basic research. But so many factors are ganging up on these beautiful fish that their survival is very tenuous.

Ocean survival has dropped off the scale in the last two decades and there does not seem to be much that can be done about it because the problem is global and beyond the control of BC or Canada. Even if a co-ordinated world effort was undertaken, resolution would be very tough. People with far more grey matter than I have strained themselves almost beyond reach looking for answers and there are many that do not even agree about the true nature of the problem. But there are things that we can do as Canadians to make sure we are doing our best for the fish.

Commercial interception in salmon net fisheries is still a huge problem. Premier world class steelhead are being killed so we can sell our salmon to the highest bidders. I have long advocated for a more controlled salmon fishery where the harvest would be more terminal and selective. This means taking more sockeye, pinks and chums and releasing more chinooks, coho and steelhead – probably all the steelhead. At one time, salmon traps were utilized along important migration corridors like Juan de Fuca Strait. This required a shared, collective effort but fishermen wanted to catch their own fish and boats and gear developed so the Wild West approach could be employed. Efforts have been made to thin the fleet and loads of fishers have been squeezed out but things have not improved much and the few fishermen left in the not so wild west are still griping in their five dollars a glass beer when they can afford a few. Meanwhile salmon farming has moved in to supply the demand. There are issues with that but I believe they can be largely mitigated or controlled.

Can a renewed collective effort of reduced or eliminated commercial interception, continued habitat improvement and protection and some kind of fish culture input start us back to a steelhead return? Perhaps but it will not be easy or anywhere near it. I can hear the howls of outrage already as I have heard them ringing off the walls for more than fifty years in my life as a salmonid biologist.

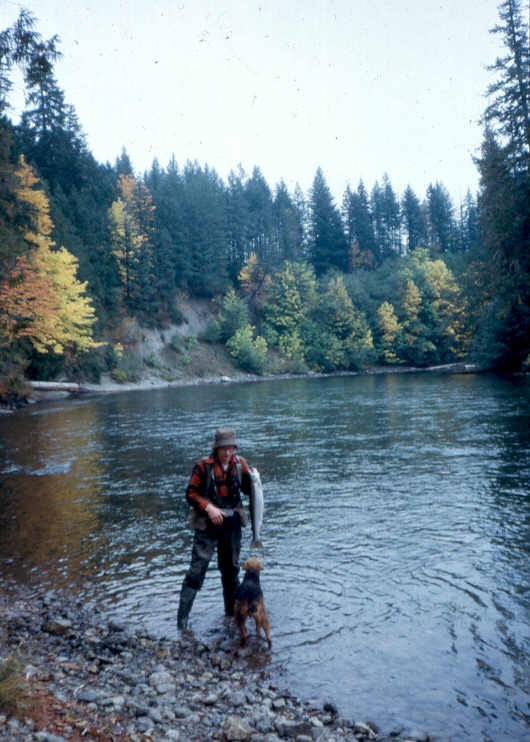

Ted Harding with a summer steelhead from Money’s Pool on the Stamp River in 1971