When I Was a Cowboy at the S Half Diamond (All my Heroes are Cowboys)

The year was 1960. I was in Grade eleven at Sunnyvale High and hated it. My friend Victor (Sonny) Simon was also a disgruntled student and his Uncle Merle Simon was buying a ranch in B C and offered Sonny and I jobs. He also offered a job to his girlfriend’s brother: Gordie Duke. Sonny and I were marginal cowboys at best but Gordie was a top hand : wiry, smart and tough.

Before we got near the ranch we had to sell a carload of Christmas trees that were cut on the ranch. We secured a lot beside the El Camino in Mountain View and set up a large tepee advertising “Royal Canadian “Christmas Trees. We bunked in the tepee and sold all of the trees at a dollar a foot. They averaged about six feet long and were beautiful. They came out of the rail cars still frozen and snow covered. People loved them.

After we cleaned out the trees, we headed north in Merle’s big Oldsmobile with summer tires. It was a cold rain when we left the Bay Area and by Shasta Lake, you could see flecks of snow on the windshield. By Southern Oregon it had switched to heavy snow and you could feel the Big Olds start to slip. At one point we spun doughnuts for half a mile or so and almost hit the ditch. This was near the small town of Chemult which is in a snow belt. Thankfully the snow let up before Spokane and it was clear to the ranch.

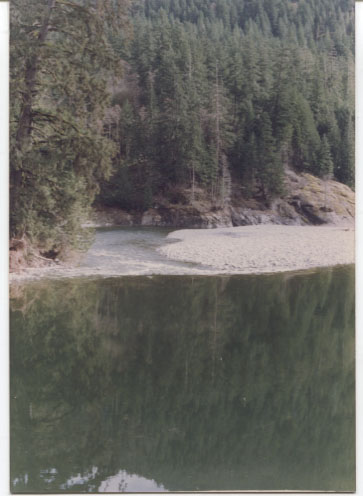

When we finally arrived there was a surprise. A big bull elk had fallen onto the ice of Premier Lake and could not get up. He had been walking on snow covered old ice where he got traction then moved out to fresh ice with light snow cover where he slipped and fell. We took a rope down to the far end of the lake where we looped it lightly around his neck and dragged him over to the old ice. He got up right away then charged me. I ran back to the new ice. As he followed, he fell again in the same spot. The ice had melted a bit where he had lain and he and I almost went through this time. We dragged him off again but this time he was too exhausted to get up so we left him. Later on he was able to get up and stagger into the woods.

Another revelation. The ranch had several cats that “sort of” lived there fending for themselves. They had a hard stretch when the boys were in California. They were huddled around the ranch chimneys probably hoping for a ghost of heat. They’re ears had frozen off !

It was very cold at the ranch in those days. The only heat was what we could muster from scrap lumber we salvaged from a little mill on the property. We had a fireplace and two wood stoves of ancient vintage. There was no insulation. One morning it was minus 52F at Bill Bush’s ranch just north of us and minus 11F in our frost covered bedroom.

The place was kind of a Dude Ranch that boarded horses for the winter. Technically we were not cowboys because there were no cows on the place. Just 40 or more horses. We were wranglers.

Apart from myself, Sonny and Gordie, there was another top hand on the ranch: Rad Hartwell a very experienced cowboy/ wrangler from down in the states. Rad and Merle were not around much that winter so we were on our own. We kept the horses in feed and water and rode them about two or three times a week. We had some great horses including a race horse named Prevail. She could run but wasn’t very sure footed and spilled occasionally. Only Gordie rode her and even he got dumped once or twice. My favorite horse was a little chestnut mare we called Square Dance. She loved to run and was very reliable.-an excellent dude horse.

We also had a big stud horse called Tom – a palomino with a white mane and a lot of spunk. He would try to kick and bite you. A horse bite can do a lot of damage. And Tom was very sneaky about it. Aside from horse duties there was not a great deal to keep us busy. Ron Kuppenbender would sometimes bring a group of Kimberley girls out to do some riding and help make supper. There were some grand girls in Kimberley in those days.

Once we found a stash of fancy liqueurs. Things like Creme de Minth, Creme De Cocao and Bailys Irish Cream. Of course we had to sample them even though we knew they were “dude “ drinks for the rich and famous and not for poor cowpokes. As the night progressed Things got a bit out of hand and someone decided that our hair was too long for hard riding bush cowboys. So out come some clippers and the massacre proceeds. We woke up in horror with pounding heads afraid to look in a mirror.

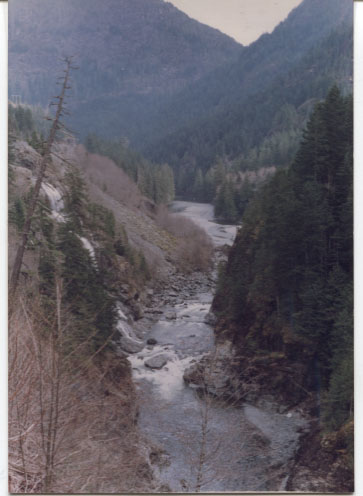

Sometime in February, it was time to get our animals off the range. The East Kootenay is often called the Serengeti of the north because of the abundant herds of big game. Deer, elk, Big Horn Sheep, Moose and grizzlies are hunted along with a few Mountain Goats. These animals depend on healthy winter ranges for survival. Horses, cattle and sheep graze out the-preferred plants and place a heavy burden on wildlife. Therefore domestic stock must skedaddle to free up the range which is often quite damaged from over grazing by the time wildlife get to it in late winter.

I think the situation is better now. Biologists like Ray DeMarchi and Glen Smith worked with the cattlemen’s groups to improve the range and more closely manage the animals.

Our horses were from two groups: Wasa and Canal Flats. This was invariably where they ended up and is was quite easy to herd them back to the ranch by following the old Stagecoach Road that ran from Cranbrook to Canal Flats There was a wild card however: the owner’s kids horses. Roddy Simon had a. large mare he called Wonder. She and her colt were hanging around Skookumchuck. We rounded them up and I volunteered to take them back to the ranch. Merle was trying out his video camera watching Wonder make a leap over a snow bank. She then galloped into the woods and bucked me off. I tried to catch her and get back on but she kept kicking and bucking. The colt was following along so a caught him and used my coat as a halter to get the two of them back close to the ranch which was several miles away through knee deep snow. Temperature was 15 below Fahrenheit degrees. Wonder got the whip when we limped back to the barn. She had been spoiled and would need a lot of riding before the dudes showed up.

After our adventures in the great Rocky Mountain Trench, I lived in Kimberley for awhile then back to Nelson and eventually we all ended up in California for a new round of adventure. I even ended up at another ranch at Mad River in the hills of Humboldt County. I never saw Sonny again but did see Gordie on occasion He ended up working on the tow boats (tugs) where he became very well known.